Governance and Stakeholding in Simple Sectors and Complex Systems

In our project’s discussions on coherent sectoral and sub-sectoral development, we often hear of a need for engagement with, and consideration of, the “tourism sector”, given that it accounts for

“more than one-third of the total global services trade… making it a significant source of employment and placing it among the world’s top creators of jobs that require varying degrees of skills and allow for quick entry into the workforce by youth, women and migrant workers.”[1]

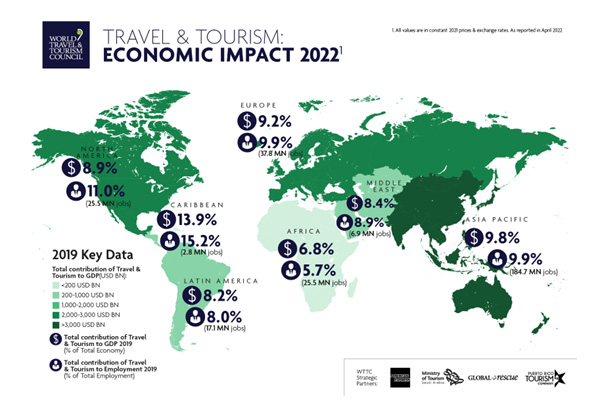

In terms of employment, it is incredibly important—prior to the pandemic the World Travel & Tourism council reported that tourism activities “(including its direct, indirect and induced impacts) accounted for 1 in 4 of all new jobs created across the world, 10.3% of all jobs, and 10.3% of global GDP”.[2]

Is the “tourism sector” the same as other sectors in an economy, and do its actors work and collaborate in the same way? This is an important consideration, in light of LbD’s sub-sectoral, bottom-up approaches and the importance of cross-sectoral support and development co-benefits in sustainable socio-economic development with a “good life”, given tourism’s employment potential throughout a country’s society.

In short, as a “sector”, tourism seems to be much more heterogeneous than other sectors, by comparison, and this has important implications in development planning.

About Other Sectors

In the “building sector”, for example, actors include developers, architects, urban planners, builders, and other technical trades relating to, inter alia, construction, insulation, and utilities. This paints a fairly coherent picture of actors who usually work individually or with each other regularly—meaning that industry-related individual or collaborative outputs generally concatenate to create consistent products. This means also that their governance and rules follow related or associated themes (the sector’s actors will generally have an awareness, if not familiarity with the governance and rules of other actors in their sector). This is broadly the case in energy, agriculture, transport, industry, and generally waste/circular sectors. Of course, there are also services delivered by these sectors—such as taxis (in transport) and waste collection (in waste), so not just goods—but by and large the clients are repetitive, and clients are also stakeholders in the improvement and progression of the sector.

So, activities that are typically part of sectors such as the “building sector” generally ultimately deal with actions on a particular physical asset, with value aggregation relatively related between the actors—one actor easily understands where in the value chain another actor works, as well as the complementary nature of other actors in the sector—the end product of their collaboration is apparent to all actors.

About Tourism – a complex sector/system

By contrast, in “tourism”, actors are of diverse industries, all dealing with a context-specific interaction to deliver what is principally a service—with material and immaterial components—to end clients who generally are not repeat customers. In tourism, often heterogeneous actors participate in the delivery of a final product that may not be visible to many of its value-creating actors, who in turn may not readily understand the alignment of other actors without the appropriate context.

So the “tourism sector” has more complexities in the relationships between its actors than other sectors, and their inter-relationship is more contextual—the correlation between the actors depends on the cooperative context of their activity, instead of a correlative linear value accretion. Another way of seeing this is that there are plural essential support activities that don’t face the final clients, which suggests that there’s only a relatively tenuous, circumstantial relationship between the members of the “tourism sector”.

On top of this, the “tourism sector” could be seen to deliver something closer to services, instead of transferable physical goods, the latter being more broadly the case of the other sectors, for the benefit of an ultimate consumer. The final client is a user of the tourism sector, although there are many value stages for services to that final client, given by many actors.

Of course, actors in the “tourism sector” can sell goods—both durable (e.g. art) and perishable (e.g. flowers) to tourism clients, but likewise these sales can happen to non-tourism clients; whereas actors, say, in the energy sector generally provide goods and services to buyers that are consistently repeat clients of their sector.

So, in tourism, we consider the airline industry as part of the “tourism sector”, however, baggage handlers, airplane technicians, and airline ticket offices have very little relationship with caterers, hotel staff, or tour guides—which are obviously also part of the “tourism sector”. To be sure, there is coordination among these actors, but their activities are normally under quite distinct lines of regulation or strategic development.

An important distinction

This characterisation is of relevance when we consider the governance and signals for a sector and its sub-sectoral actors when we seek to align self-interested actions in a transition to a sustainable future. More to the point, we need to ensure that initiatives that promote particular inter-sectoral, or “system” development, don’t work at cross-purposes to the broader goals and measures of the underlying simple sectors. A conflict or divergence of perceived benefits to actors that may see themselves in more than one “sector” would undermine efficient transition paths to a “good life” at net zero, adapted to the environment.

Actions and governance in complex sectors

In the LbD project, we’ve considered collaborative agency by sub-sectoral actors as paramount in the collective transition of sectors, yet when we consider “systems” of these actors, in activities which are more complex with other actors not in their immediate sector, the governance of actors in the “system” may not be homogenous.

This is important because governance of the “tourism sector” may be sought through tangential initiatives, which try to gather particular instances of action which affect one or more of the simpler sectors, but with a different optic. For instance, in our project, we have come across situations where a country wishes to advance, or coordinate, its “tourism sector”, but the first step for this is in relation to say land-use ordinances—which notionally may have better association with urbanism, agriculture, or other sectors. Thus, we may arrive to situations where the sustainability measures in the broader simple sectors may be at cross-purpose with aims or demands of selective actions for a complex system such as the “tourism sector”.

Why would rules for say urbanism be labelled as pertaining to “tourism”, when their logical scope should be on land rights and infrastructure? Perhaps because economic activity and investment in tourism may be more relevant for short-term economic development than activities in agriculture, or urban development. The result of this anomaly may be that rules and aims in the more dynamic activities simply take over the rules and aims of the background, broader, less dynamic sectors—without necessarily generating a better life for all. Ultimately, this anachronism means that infrastructure and other necessities for broad development become obscured by immediate policies considering the more dynamic “system” development—the “system” becomes more important than the “sector”.

A compounding element to this is that the end clients of this complex sector, or “system”, are non-recurring and so not stakeholders in the sustainable development of the system. They are, quite literally, tourists to the system. This can create a supply-side competition in the system to circumvent broader safeguards for sustainability in medium to long term development.

Safeguards for a complex sector/system

Provided the importance of background sectoral development is respected—and no “special regime” with unaligned rules or practices overrides those priorities—there’s no reason why a complex sector/system can’t work within rules designed to support a good life for all—and not just for certain operators in a system. This can work if the final aim/vision of the complex system and its actors is aligned with the final aim/vision of the underlying simple sectors.

This hierarchy is important to acknowledge—that the fundamental sectors must govern the complex, and not vice versa—as the complex system cannot work sustainably if the underlying, supporting sectors aren’t working sustainably on their own terms.

The governance risk considerations are important to keep in mind—complex sectors/systems may be more economically dynamic than broader sectors, implying that broader, traditional sectors may thereby be considered the servants, say, to the tourism sector, which latter sector is more mercenary in its operation as its clients generally have no stake in its sustainability. This ultimately implies that governance may move to cater to non-stakeholder, mercenary clients—with deleterious effects to the underlying simple sectors.

A solution is the involvement of the clients of the tourism sector as stakeholders to its sustainability. Indeed, it would seem important to consider a pact of sorts for tourism clients that touch the natural environment; this wouldn’t be so important in tourism within a built environment, as the impact of those tourists would be no different than other citizens’.

What we can look to do is to bring the background to the forefront—to move growth back from selective cross-sectoral industry groups, to development patterns that include broader sections of the economy, supporting them to a collective pathway to a “good life” in a sustainable emissions and adaptation envelope for all. This may imply a balancing of the drivers towards local development, to ensure that the “system” benefits the broader background sectors in their transition to a “good life” for all in the context of emissions and adaptation of a 2-1.5˚ society.

We must be wary of special building, consumption, or zoning code for systems, as this may create competition or incentives for “gaming” the codes. Another way of looking at this is that we can’t sustainably create incentives for construction of “tourism” buildings which are different than non-tourism buildings; this creates an incentive to do strategic differentiation at the delivery stage, so planning, conceptualisation, and other considerations for use don’t align, or become twisted.

Gilberto Arias, London, 2023.

[1] See ILO: https://bit.ly/3veEdK5

[2] See WTTC Economic Impact Reports: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact