I. Backdrop and Aims of Learning by Doing

In any language, by any measure, it’s a tall order.

Historically, barring religious commitments, human development has been about prioritising personal outcomes—yet our success in improving our individual condition has moved us to a position where we must weigh these instincts against real societal, and planetary, consequences, as our sustained, collective, incremental actions have come to affect our societies and our collective future.

At heart is the issue that for the first time in human history we’re faced with collective, not just personal, consequences of broadly individual actions and general practices. If the densification of populations in close quarters became toxic until the development of appropriate sewerage systems, we’re now scaling the same problem to a planetary scale.

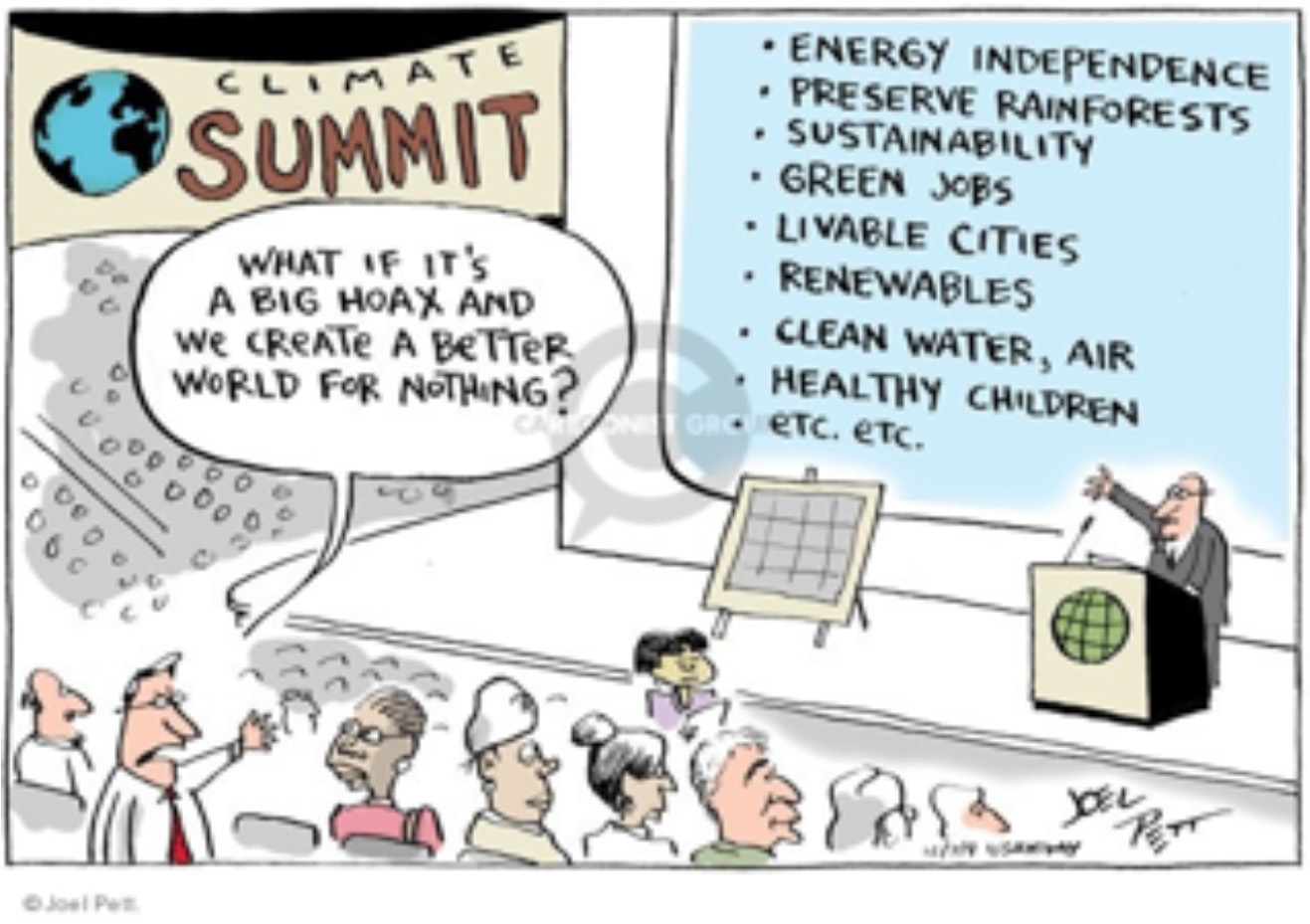

How do we guide our common knowledge, common perceptions, and practical wisdom, to internalise costs which are traditionally, systemically externalised?

If in a policy spectrum we have options which are, in the short term easier or cheaper—because of the exclusion of long-term costs—but in the long term far costlier in social terms, how do we reduce the myopia of long-term consequences stemming from short-term individual priorities, which has also led to a malaise of hugely disparate development silos?

How do we present total-cost-of-ownership (TCO) criteria for societal infrastructure? This requires a perspective of long-term responsibility, and of long-term stake-holding, but in developing countries, where pressing needs for political attention are in the much nearer term, this perspective may consistently fall through the cracks. Some of these issues may be addressed with longer term credit risk for the country, however, many other influences also affect simple “country risk” data, so this is an imperfect indicator.

The challenge of transforming, or moving away from, extractive and exploitative natural, economic, and social practices—which have not produced motivated, collective repercussions priorly—is now crucial, as we approach not only natural planetary system boundaries, but also the repercussions from testing these planetary, and social, boundaries as our population, our increasing longevity, and our projected current practices create further effects.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report for 2022[1] notes:

For the next five years, respondents again signal societal and environmental risks as the most concerning. However, over a 10-year horizon, the health of the planet dominates concerns: environmental risks are perceived to be the five most critical long-term threats to the world as well as the most potentially damaging to people and planet, with “climate action failure”, “extreme weather”, and “biodiversity loss” ranking as the top three most severe risks. Respondents also signalled “debt crises” and “geoeconomic confrontations” as among the most severe risks over the next 10 years.

All countries have a responsibility to engage and take action with the problem in their national interest in line with the science.

What’s in it for all of us, what’s possible, what’s the future including these considerations that can be better, and how can we get there? These are the fundamental questions of LbD.

As was noted in a recent G7 report:[2]

Over the next few decades, the most significant risks are not other single-source crises like the pandemic, but some combination of adverse environmental, health, geo-political and socio-economic events. Future resilience is already under pressure because of ageing populations, the debt burden, the scale and scope of the green transition, cyber security threats, and adapting to the climate impacts already locked in.

For a “good life”, societies need to prepare for these risks, and develop a matrix that is resilient to these and the accompanying social pressure that these conditions will create—all within a paradigm of environmental husbandry.

It’s clear that we need to consider a “good life” or sustained future development, with a view to resilience to a number of compounded external and internal, environmental and social, factors.

Conventional wisdom has constrained economic policy and failed to produce resilient economies – a failure that has been exacerbated and exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. A new consensus is needed that prioritises the role of governments in shaping economies and public-private partnerships that put the goal of resilient, sustainable and inclusive economies front and centre.[3]

These insights confirm our project’s guiding construct that a bottom-up approach to sustainable development and a future Paris-aligned, resilient, attractive society, needs to look to a broader basket of outcomes for policy. The transition to a low carbon society, to gain traction, must address a broad set of issues to be actively and quickly adopted by societies—it can’t be simply focused on energy, emissions, or electric vehicles, for example.

Political Will

Stakeholders concerned with future impacts decry a lack of political will, or not enough leadership, from political actors around the world. In current, razor-thin majority democracies, policies developed for the broadest swathe, or broad groups within the supporters of these leaders, is simply not advancing on climate-relevant topics at the speed that is required in enough of the world. Indeed, it may not be a far stretch to say that broad development topics, such as enhanced education, inclusion, and other SDG topics, are equally not advancing with global needs.

Even when we do find political will, say where business and popular interests align—for example in the energy sector—that change can happen; however, in many cases, this is a supply-side change, which bring its own limitations. Given that these industries in many cases operate as a small group—often less than five or ten relevant firms per country—climate-aware policies may be mooted across a spectrum which isn’t compatible with considerations of social and economic risks in the longer term. For example, a policy supply-stakeholder decision may postulate choosing between having 10% more renewable energy vs. 10% more coal power, whereas a decision-spectrum more aligned with sustainable development and limiting future risks may choose between 15% more renewable energy vs. 5% more renewable energy. So the future constraints may not be presented in a coherent way, meaning that “ambitious outcomes” are, from a perspective outside those actors—let alone from the perspective of science—not all that ambitious towards climate-change-aware ends.

Therefore, the options which leaders seem to be choosing from—which by almost default will be a “middle” or “conservative” course from the options before them—are generally based on BAU, and not from the choice horizon which science may propose. In other words, “ambitious” is viewed against the perspective of BAU, and not against the outcomes required by science.

Reality, economics, and lock-in make the transition to the science-based options, particularly in the speed required, difficult.

In a more concrete example, and referring to cars and mobility, particularly ascendant in Latin America, we have the challenge that as wealth increases, the proportion of trips made by private light duty vehicles also increases, whereas in actuality, we need to move to paradigms where these sorts of trips are reduced. A recent report notes that the number of light-duty vehicles in the world will grow by 100m vehicles by 2030, which number may be principally in the developing world. If we factor in a 12+ year life expectancy for these vehicles, it’s clear that many things have to fall in place—not just fiscal incentives, but demand for shared vehicle mobility, or better and more attractive, inclusive, opportunities for other mobility solutions.

The obvious challenge is in articulating a demand for a different way of dealing with societal needs, with speed, so that the solutions that politicians can feel will get them elected are framed within an envelope of actual sustainable development, and not from a meager option of millimetrically incremental measures which are shown as “progressive” because they diverge from existing BAU incremental measures promoting a high carbon, mal-adjusted, extractive, exclusive societies. In LbD, we thread these concepts into the framework of transition.

For a political change to happen in democracies, leaders must register demand from their stakeholders for solutions which align with Paris-type trajectories, adaptation to climate impacts of a 2-1.5˚C world, and inclusive, sustainable development. These options for solutions must be from a spectrum of ambition to these goals, but not including options which patently avoid or delay those outcomes.

As Nikos Stafos of the Center for Strategic International Studies puts it,[7] “It’s very easy to solve climate change if I’m not politically constrained.”

Transformative change in key sectors can’t be timid any longer—it’s almost like we can no longer be “cautious”, but we must be “intelligent”—and “intelligent” now no longer means timid. We can’t fall into the trap of “ambition” being compared to BAU; “ambition” can no longer be seen entirely subjectively—it must stand the reflection of objective science; it must be geared to the actual necessities to be delivered.

Walking the Walk

Transformative change along the lines we’re discussing requires an exploration of some degree of systemic changes, particularly in light of the broad buy-in required for advancement.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that the transition will be orderly.

To paraphrase Lao Tzu, it’s unreasonable to think that in the journey of a thousand miles you won’t get blisters.

We can’t have the leaders of 200 nations all agree that the planet is more important than their re-election. We may get some, we may get many, but we won’t get all. This is the challenge, and this is the problem with a multilateral consensus mechanism, where the most ambitious outcome will not ensure permanence of the status quo for the governing and empowered elites in the near term.

Thus, we’re seeing more results from the COP coming from the sidelines, from “clubs”, than from the COP outcomes.

It’s clear that BAU affects the earth, and it’s clear that inaction affects the earth, therefore, any conception of intelligent political leadership with any perspective beyond myopic wealth extraction must engage with this perspective.

The extent to an existing passive, negligent, or reckless approach to future costs is highlighted by the economist Partha Dasgupta, who has estimated that the annual global cost of all environmentally damaging subsidies (including for agriculture, fisheries, fuel, and water) is somewhere between $4 trillion and $6 trillion. By contrast, governments devote only $68 billion annually to global conservation and sustainability—about what their citizens spend every year on ice cream.

Our aim in LbD is not to dictate a pathway, but to inquire on a vision which allows us to look at our current obstacles in a new way, and to appreciate and consider linkages between sectors and societal needs, not constrained necessarily by where we are, but for where we want to get to. In this way, LbD seeks to put the most efficient roadmap to that future, as it would take interactions between sectors, and needs of places and populations, into account from its inception.

II. Insights from the Project

Considering pathways, the scrums we’ve had, participants really don’t mention much on technology. It seems that technological advancement is either considered a given, or not relevant to the underlying issues that are important.

We may need to consider strategies revolving around early adoption of technologies and solutions processes. A Dominican scrum participant mentioned that in an action in a target community, education and capacity-building for villagers regarding the consequences of dumping animal and human waste into the local river resulted in a change of the water and air quality of the area within three years.

This is an example of a principally capacity-building/education/awareness-raising “early adoption” movement, which required little in the way of technology, but plenty in the way of education and capacity-building, and has the benefit of being bottom-up and easily replicated.

The Journey Ahead

In the face of the political challenge to leadership, support from policy stakeholders needs to demand a necessity for action now. And to have this desire for action encompass all, or most avenues of climate action, it must go beyond a strictly climate agenda to have broad buy-in. We must consider, and propose, an ambitious outcome beyond de minimis climate action, or else understand that we will face a statistically predictable increased accumulation of risks, which would require a different time horizon and discount rate than currently guide investment and policy decisions.[9]

A transition involving decades-old practices, in short order, without assured immediate benefits to those who make the shifts—is a tough sell. But this is our reality for the journey ahead.

This is why even enlightened self-interest is probably not enough to achieve net-zero—we need something to draw us to that society, and this in turn generate support for political leadership required for a more orderly transition.

There’s no question that these changes will affect most daily lives—the challenge is that it be for the better. And climate change will definitely affect for the worse in all cases, which, if unmanaged, unprepared, or not communicated properly, could lead to public backlash consequences such as migration, civil disorder, and societal fragility.

From the scrums we’ve had across the project, and from our review of practice literature, we note that much attention has been focused on technologies, and technological innovation and scaling—which gives observers a conception that someone else will provide and manage a solution,[10] and greatly increases the risk of blind spots for requirements for local adoption and implementation. In particular, understanding and preparing to address the socioeconomic impacts of the transition appears to be a critical step, as perceived transition costs and effects would cause opposition, and unacceptable delay, leading to inadequate or imbalanced adoption, which would in turn lead to instability, migration, and other tail-end resolutions. This is the requirement of a just transition—and the transition must move quickly—it’s no uses to navigate through rocks and currents of opposition, only to then founder on shoals of insidious apathy.

There are no simple answers, no golden measures for these changes—and every country, every region, will have its particular nuances. Re-working how we do things, and to some extent our economies, is a huge undertaking and will require global participation, especially in the time frames that we have before us. Specific practices will evolve over time, as new patterns of trade and capacity, and technologies emerge, yet all stakeholders must be on the journey. Policy-builders, academics, producers, finance sectors—all must be involved in the transition, including understanding the fundamentals of climate science and the impacts, and cost, stemming from inaction. Moreover, for it to have this broad an uptake, the transition must overlap other sectors—in other words, we can’t allow other sectors or interests to delay the climate transition, so the transition to sustainable development must include climate change, but must also include other considerations—all aligned to a Paris-compliant society, adjusted to impacts, and attending to social needs.

By way of example, advancement towards improved practices in the agriculture sector, including nature-based solutions, attention to biodiversity, and implementation of climate-conscious innovations, requires capacity-building, and effective changes in practices across many levels of intensity. And, of course, changes would need to be married to links with other suppliers and off-takers, and the development of circular economies in the sector, which is another tier of education and capacity-building to be accelerated.

This notion of capacity-building extends to things, practices, as elemental as water use—especially in the agricultural space, alongside industrial uses, and also in waste water management, again, not just in urban or industrial contexts, but again, in agricultural contexts in peri-urban and rural communities.

How big is the ask?

The big investment shift we’re looking at in the transition is larger than we can easily process, because of the perspective required.

“Forthcoming estimates by McKinsey based on a scenario limiting warming to 1.5˚C and reaching net zero by 2050 from the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) suggest that spending on physical assets across energy- and land-use sustems would substantially increase and shift relative to today. In our current estimation, the net-zero 2050 scenario would entail spending on physical massets of $9.2 trillion per year on energy- and land-use systems until 2050. This represents $3.5 trillion more than the current annual spending in these areas, all of which would need to be spent in the future on low-emissions assets. This incremental spend is equivalent to about half of global corporate profits, 7 percent of household spending, represents a quarter of total tax revenue, and is about 20 percent higher than the average annual increase in public debt seen between 2005 and 2020. If we consider the likely evolution of this spend, given population growth, GDP growth, and current momentum toward the net-zero transition, the capital outlay would be smaller but remain significant.” (Emphasis added)[11]

Although daunting, we have evidence that even this degree of investment is not a pipe dream—as has been shown by the degree of public interventions in the 2008 financial crisis[12], amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars in the US alone, and in the COVID pandemic.[13] Although, again, the figures are truly large, we must take their reality on board, for, as the European Central Bank has noted, “the short-term costs of the transition pale in comparison to the costs of unfettered climate change in the medium to long term.”[14]

In many sectors there may well be overall savings as a whole, as many climate change and sustainable development investments are cost-effective and would yield a return given a long enough repayment period, particularly when previously avoided costs and externalities are included.

Of course, capital-attraction and risk normalisation would be required in the short term, to give immediacy to the long-term signals hidden in climate change action horizons, and the conditions for attracting capital will vary around the world. Attracting capital to these projects and initiatives will include preparation, such as awareness-raising of risks, capital-pricing mechanisms aligned with overall risks, and even sovereign support to ramp down certain investments, and ramp up others.

A Just Transition

The transition to sustainable development will have different speeds and impacts around the world, with varying social and economic dynamics at regional and sub-national levels—conditions and needs will vary from area to area. Of course, a projected fall in demand for high-carbon products, and an increased demand for products and technologies conscious of sustainable development implies a reallocation of capital and labour, of new new vectors for diversification—which may affect both public and private revenues. A relocation of productive capital would also include work required in the transformation of capital assets, and the parallel re-skilling of labour, civil society, and the productive sector towards new, or newer, activities—which would also require updating orientation of political leadership towards the transition towards longer term goals. Remember that the transition is a pathway, not a destination—the destination is the resilient, well-adjusted, Paris-aligned society that is attractive enough to create demand for the transition.

These changes require the reassurance of transitional justice, or at the very least a voice or a hope for transitional justice and support; without such buy-in, impacts of the transition are likely to be regressive, with poorer communities carrying a greater burden—this would create well-founded opposition to change, which could slow transitions.

These aims need to be considered with the same urgency and focus as say the transition in the energy sector.

How do these needs get articulated to political leadership in order the right pathway and speed options to be considered? It seems imperative that the physical risks of traditional development pathways be underlined clearly and graphically. Incentivising citizen “pull” for the new technologies and practices is essential. There’s an essential need for awareness, but also for people trying different ways of doing things, and communicating results and preferences.

The project has suggested that we may need fora and platforms for dialogue on these issues, to look for, and identify blind spots in top-down development discussions. It’s important for societies to be aware of where BAU is taking us, in very concrete and palpable terms, including what are now tail-end possibilities. Understanding of the consequences of inaction is a necessary step for communities to go beyond de minimis, and a promise of a broader agenda for sustainable development—towards a “good life” is essential for moving ambition to this change in a meaningful way: that is, not centred on BAU, but focused on the type of deflection that science calls for.

In the LbD project, reflecting on these questions, we’ve received interest in the establishment, or development, of South-South networks regarding capacity-building and skill discovery for the new role that communities need to find in a Paris-aligned, non-extractive global economy. This includes the development of an ecosystem which includes academia, production and trade systems, as well as communications and know-how on new trade/supply patterns to encompass such things as circular economies, or agricultural efficiency improvements. This space would include investors, the finance sector, know-how and technology providers, and local innovation, towards an aim of creating conditions for the uptake of new production and consumption paradigms, and opportunities in environmentally conscious communities. Importantly, much can be advanced using local initiatives, so as to deliver opportunities in a decentralised way, with an order that works for the local communities, resources, and existing or acquired skills.

Following from our LbD exercise, there is no magical codex—communities must design and build their own solutions—and the solutions and proposals can evolve iteratively, with organic opportunities for growth and replication. Not all activities will exist in every place, but new activities will have niches and opportunities, with the challenges we’ve discussed throughout this note.

Possible outcomes visualised in LbD

When considering a future society, it’s possible for participants to overlook what are actually popular and desirable outcomes because they, possibly incorrectly, believe that the majority of thinking is not following their logic or point of view.[15]

However, it’s important to consider that the exercise that we follow in LbD isn’t one of projecting the present, but one of re-imagining a future for the object society.

As such, considerations of greater or lesser centralisation came up in discussions—both for public and for private social services—often arising from a reflection of how communities had evolved during the COVID pandemic.

While it’s simpler to develop an architecture for needs-fulfilment using a top-down approach, the COVID pandemic and other experiences in recent societal memory suggest that the current greater popular diversity of opinion, even polarisation, on political direction may request an inclusion of bottom-up approaches to needs-fulfilment, not only in terms of attending to particular grassroots sentiments, but perhaps more so in terms of a future world where highly localised issues, such as climate adaptation or nature-based services become increasingly relevant.

As such, we may pull some of the strands mentioned—particularly in our discussion of avenues to system change—where certain alternative scenarios seem to well up.

For example, if we follow the propositions to a more decentralised future, this would mean the reduction of centralised policy—but not necessarily in all ambits of public activity. What sections or practices are decentralised, and how do we plan or implement a transition to this decentralisation? This returns us to the question of how a society fulfils needs, and then looking at these in a hierarchy to understand which make sense to decentralise, and what community capacity-building, is needed for the decentralisation to happen. This exercise then begins to outline a pathway to the target social conventions of a sustainable Paris-aligned society.

In this reflection, it’s clear that there’s not one, single approach to “a prosperous society” for all circumstances, as even within a single jurisdiction, it’s imperative to nurture different approaches to sustainability—these elements will depend on cultural nuances, as well as local natural and built infrastructure. A coastal community will have concerns, traditions, and practices related to the sea, which will require different priorities to a community inland, for example. So, equally, there’s no single pathway for a “just transition”.

Given various possible action options for society, we must try to ensure that choices aren’t “gamed” and that folks moving away from one bad practice simply don’t switch to another bad practice.

For example, it may not make sense to simply replace every petrol-driven vehicle with a hybrid vehicle, when other mobility options exist. Moreover, even hybrid vehicles include legacy components—meaning that fossil-fuel jobs that must be sunsetted, and the economies of low maintenance associated with EVs, aren’t exposed.

Thus, in the transition, we not only have practices and technologies that societies must prepare for and take up, but equally, there are technologies and practices that societies must actively move away from. They must be taken together in order to overcome development challenges which will only become much more accentuated under business-as-usual projections.

Moreover, a “just transition” must be seen as really attractive by a broad segment of the population for it to be functional in the time frame that we’re dealing with. “Attractive” in terms of needs fulfilment, culture, opportunity, and security.

Yet there’s more to this transition than a transition in energy systems, or in transport and mobility—even though these two elements are mammoth tasks in their own rights.

Therefore, like a move to circular economies—which we’ll discuss later—the transition isn’t a one-step change in development, but more of an inexorable slide across a series of stages, with different options becoming available over time, progressively.

We need to consider the pathway of the transition—what in some of our discussions we’ve called the “inflection points” on the transition.

These “inflection points” include socio-political components, but there’s an essential element of enabling capacity-building towards the uptake of solutions—and baseline capacities for adoption of technologies or practices is not homogenous across the world.

It could be that resistance to change in non-economic indicators can be affected by information, and knowledge of options, from stakeholders that may affect decisions in the principal group.

Indeed, private-sector innovation partnerships, which can include academia, sub-national actors, and cooperative sectoral initiatives, have a distinct role to play in accelerated movement to sustainable development[16]—and the multilateral sector is transitioning to support these sorts of initiatives—this is one of the acceleration points of inflection that the transition requires.

As is noted in the tenor of these developments, there’s a growing recognition that the speed required, and the breadth of action needed, outstrips national and even concerted multilateral capacity alone—the private sector must be drafted to accelerated action.

Part of the exercise is for participants to review their previous experiences and to see how good and bad lessons can be extracted from those experiences towards components of a better society, and to changes or pathways to that society.

Many participants mentioned accelerated social changes brought on through social media, as well as the pandemic experience—which highlighted elements which were mentioned as looking to be leveraged or amplified, as well as distanced from.

The changes that are becoming apparent in our scrum discussions include considerations of transitions to re-manufacturing, instead of extractive importation-use-landfill processes for value creation, transitions of human capital to the new skills required in sustainable societies and industries, transitions of capital to risk profiles aligned with climate and social concerns, and transition in readiness and capacities for the uptake of new, climate-conscious practices and technologies—for example in agriculture, urban planning, mobility, etc..

By and large, these follow an insight that technology in and of itself is not the answer, as there can be gatekeeper issues that present challenges to inclusion or access to the technologies, or barriers to adoption, which would slow down the uptake even when the technology is available. The point of new technologies is to use them optimally and efficiently, not to use then only for the sake of their novelty—if not planned or managed correctly, EV’s could create their own manner of toxic waste in the recipient countries, for example, and contribute to an accelerated, unsustainable, extractive industry for their mineral sources.

One of the insights that we underline in the project is the subsidiary role of technology to social capacity-building for the uptake of new processes, practices, and development pathways.

Inclusion Inequality and Opportunity

Another facet of the discussion for “change” amongst the scrum participants is the request for considerations of inclusion in future economic development—arising from concerns around inequality and lack of opportunities across societies—particularly in light of how participants could view a “good life” in the future.

In the post-pandemic vision of economic reconstruction, these questions are seen perhaps in a new light, where possibilities are feasible that may have been unthinkable if societies had not endured the examination of value propositions, and the new paradigms for industry and production that have come about. For example, once the “work from home” genie is out of the bottle, the location of “home” becomes very fluid. In Central London, certain previously in-person services were now being done remotely—even from other countries. An extension of the concept of call center, but now completely leveraged to many more areas.

Is this an avenue of inclusion in economic development? Has the pandemic given a glimpse to ways in which more people can provide services, or has this opened a race to lowering wage offers by unscrupulous firms? The answer to these questions will turn on whether the firms are operating in an extractive mind-set, which is demonstrably unsustainable in the middle to long term, or as a vehicle to enhance value delivery.

In this period of pandemics, there’s equally been introspection about the wealth extraction that can come from innovation—particularly if innovation delivers a new form of monopoly practice, where the channel to the merchant effectively limits the ability of suppliers to compete and provide services. In other words, the monopolisation of the client-service channel may throttle the ability for innovation, unless it’s at the channel-owner’s initiative. This, in turn, confirms that the channel’s clients will only receive the channel’s offering—which becomes quite captive.

The project is discussing issues of how to consider rewarding innovation in a way that supports public affluence. Also, if we want to consider a trampoline for innovation, we must also consider safety nets as a part of public affluence—these are similar considerations to what we’re discussing in terms of “good life”, as “good life” must be considered beyond simple economic or emissions indicators, but include not only societal needs, but also consider common aspirations—otherwise, proposals will indeed appear “tone deaf” to the target participants.

We have, in this vein, heard a common comment on inclusivity, which reflects an interest in supporting sustainable prosperity in middle and lower socio-economic classes, and from there to move forward in social development.

Collaterally, this notion of mobility and inclusivity can be translated to the perceived need to create opportunities outside of the capital city. This is politically a difficult proposition, as there are fewer votes outside the capital, yet it’s paramount that opportunities exist in rural areas if a functional and harmonious society is to be.

As was noted in Dominican Republic, there may be an opportunity to link academia with innovation in rural areas, and to use this as a low-cost springboard for rural development.

Of course, any such initiative would need to have inclusive planning and stakeholder involvement—from resource-funding, implementation, and local stakeholders—to ensure real, palpable, if evolving (but sustained) results to a long-term goal—and not simply a populistic measure for short term commercial or political aims in the rural area.

The reality of opportunities and innovation away from the capital needs to be credible if it’s to nurture the desired outcomes—even if rural innovations provide services to the capital—and that the infrastructure to take care of social needs in rural areas is at least equivalent to infrastructure for social needs at the capital.

For inclusion in a somewhat more decentralised development model, especially for inclusion away from the capital, it becomes imperative to have good information exchange about what markets are looking for, so development and innovation can serve both local and distant opportunities.

Stepping Stones and Inflection Phases

When we look to describe the “stepping stones” for the transformation to adapted, inclusive societies within a Paris-aligned 2-1.5˚C world, we can visualise particular milestones, or phases, where practices change or technologies are adopted—we refer to these as “inflections”. Note that in our modelling, to be developed later in the project, we can study the changes in costs to having earlier or later inflections, and how these changes affect and interplay the sectoral stories within the broader transition narrative.

From a present-day perspective, inflections can be seen as catalysts for change, and subsequently, in retrospect, as the effect of changes happening—but in no case are they accidental, as BAU, which has no inflections, is enormously inertial. It’s important to understand that points of inflection require enabling circumstances, which can be technological, social, economic, or political—and often a combination—and better enablement can yield accelerated uptake.

Some points of inflection can be of movement towards certain circumstances or practices, and other points of inflection can be of movement away from certain circumstances or practices; both types of inflection require appropriate enabling characteristics.

So, commonly we’ve heard suggestions of positive points of change—for example, regarding the adoption of EVs, retrofitting building insulation, or switching to renewable energy, and the requirements for uptake of these, which include infrastructure enablement and pricing incentives. Adopting these requires “soft” capacities and competences, including awareness-raising for enabling capacities, such as training for installation and maintenance, training for local engineering capacity to deliver, as well as “hard” capacities, such as uprating grid infrastructure to manage the new technologies, or the development and education on labelling guides in the supply chain and for implementation—these would be enabling elements of the inflections.

Moreover, in the transition to a Paris-aligned 2-1.5˚C world, there are practices and technologies that communities need to move away from—and these changes also have their own particular stepping stones and inflection points; in other words, they may not happen in one step. This can be in terms of sustainable consumption and production, waste management, and water services, for example. Curiously, to the extent that these “moving away” stepping stones may be inertial BAU elements, then the awareness-raising for these “moving away” points of inflection are also important.

By way of example, and poignant in our discussion, much has been written of the speed at which new technologies can replace older technologies—for example, in communications or transport. However, it’s clear that certain physical or cultural infrastructure must be in place for these changes to actually be taken up at speed. For communications, there was the requirement of wireless connectivity infrastructure; for transport—to petrol motor cars—there was the requirement of filling stations and mechanical garages to support the adoption of the new technology. Therefore, the simple introduction of a new technology to an unprepared or unaccepting society will not achieve the desired speed of uptake—this is what we look to capture in the concept of phases of inflection—a preparatory, enabling, or competence-building phase that supports the actual inflection desired in a change.

If we want to move, or if we want to count on, exponential uptake of particular practices or technologies, we need to ensure that the conditions—capacities, infrastructure—for such uptake are present, in order for demand to fuel the transformation, or, in the case of consumer countries, for the practices and technologies to effectively replace the practices and technologies that are no longer functional for a Paris-aligned society in prosperity within a 2-1.5˚ world. And it’s clear that these inflections may not happen in single steps—for example, where new practices need to be created, and where the size of a given market needs to exist in order for a new practice to be adopted—for example, for new activities for circular economies, which in many cases may be entirely new activities in the object community, and may require a number of steps from input to final output to justify the complete adoption of the practice, or “practice package” where more than one practice must be aggregated for the desired inflection[17].

Of course, there will be situations where we have a negative inflection and a positive inflection happening simultaneously, but, given that there are many options for societies to act, and there may be many legacy incentives (and interests) to deal with, this may not always be the case.

In practice, actors in society have a variety of different options to act, which may not imply a direct substitution of one practice or technology to a preferred practice for a Paris-compliant society. For example, a family with three large fossil-fuel cars may move to two hybrid and one fossil-fuel car, instead of reconsidering mobility options through a broader lens—and still feel that it’s moving to a sustainable future. Yet this transition would not be very ambitious, given that the cars would be locked in—along with their required energy and support infrastructure—for an average of twelve years, or more. What could happen is a move to one or two hybrid or BEVs, with an uptake of alternative mobility solutions, or a reduction to a single BEV, plus perhaps an intelligent ride-sharing component and alternative mobility—the benefit being that there’s less footprint for idle vehicles either in the city or at home.

In this last example, we see a positive uptake of a replacement technology—the BEV or hybrid vehicles, which we’ve called a “positive inflection”—and a reduction of penetration of single-user vehicles, which we’ve called a “negative inflection”.

The speed at which we can move ambitiously is largely determined by the enabling environment for the uptake of the sustainable technology or practice, including subsidies and fiscal incentives (when functional)—and not simply by the existence of the alternative.

Elements that we can describe as “negative inflections” are turning points for the optimal Paris-compliant society which sunset unsustainable BAU practices. By way of example, these would be socio-economic constructs which would align with extractive development pathways, or practices of an extractive economic model, which should be sunsetted in the transition to a sustainable development pathway. A fast-track transition would not only promote positive inflections, but also accelerate opportunities to project negative inflections—communicating and highlighting the consequences of both, and the necessity to accelerate the sunsetting of the latter.

By another light, the transition must examine practices and activities which are prevalent under BAU, but which need to be disincentivised in the pathway to a future functional society. These elements aren’t always readily apparent—essentially because some norms follow practices from well established industries and supply chains. Practices that need to change may not always be of first-order low-carbon activities, for example on energy efficiency, incorporation of renewable energy, or scope 2 or 3 emissions tracking, but may have to do with nature-based services, or wastewater management—issues which require re-orientation and education, and not just hardware.

Some “negative inflections” can be addressed by legislation, however, given the sensitive nature of transitions, the project notes that it makes sense to consider these concepts of negative inflection hand in hand with policies and orientation towards positive inflections, so as to provide opportunities for prosperity to affected parties.

Like positive inflections, for negative inflections there’s a degree of education and awareness-raising that’s essential, as often BAU practices continue because of ignorance of options, or from the inertia of practices which are considered “least cost” because of their non-consideration of important social or environmental externalities. In the best of cases, negative inflections become supports for positive inflections—and are equally relevant.

The project will consider different phases of inflection as the participating countries consider their own development pathways, which will have positive and negative inflections. These are under consideration in topics such as public affluence, and deeper discussion on 2-1.5˚ futures, and related to topics such as sustainable consumption, which deals with the concept of practices we’ve discussed, and how solidarity for a common good can be messaged. Likewise, in the agricultural sector, inflections on considerations of natural systems, and the use of nature-based systems from rural to urban contexts are apparent in the scrums discussions.

Even in the area of urban planning, inflections must include new initiatives and considerations in concepts such as optimisation of urban planning, and integration of mobility options, and inclusion of opportunities and innovation across socio-economic strata. On opportunities, scrums will also discuss considerations of the development of opportunities in areas away from capital cities, in particular, in rural areas, or in areas which must move away from high-carbon, or extractive, practices and industries.

Alongside this will be considerations of local institutions, and discussion about how these institutions work to deliver multi-dimensional development, as was noted in the G7 report mentioned at the outset of this note.

* * *

[1]. See https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2022.pdf

[2]. G7 Panel on Economic Resilience. (2021). Global Economic Resilience: Building Forward Better: The Cornwall Consensus and Policy Recommendations. (Sedwill, M., Wilkins, C., Philippon, T., Mildner, S-A., Mazzucato, M., Kanehara, N., Wong, F. & Wieser, T., Eds.)

[3]. Ibid.

[4]. See Roque, Daniela, and Houshmand E. Masoumi. ‘An Analysis of Car Ownership in Latin American Cities: A Perspective for Future Research’. Periodica Polytechnica Transportation Engineering 44, no. 1 (2016): 5–12. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPtr.8307.

[5]. Forum, International Transport. ‘ITF Transport Outlook 2021’, 2021. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/16826a30-en.

[6]. See Page 90; ‘BNEF EVO Report 2020 | BloombergNEF | Bloomberg Finance LP’. Accessed 10 January 2022. https://about.bnef.com/electric-vehicle-outlook-2020/.

[7]. Rathi, Akshat, and Will Mathis. ‘Germany Quitting Nuclear Doesn’t Doom the Energy Transition – BNN Bloomberg’. BNN Bloomberg. Accessed 11 January 2022. https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/germany-quitting-nuclear-doesn-t-doom-the-energy-transition-1.1705902.

[8] ‘The International Order Isn’t Ready for the Climate Crisis | Foreign Affairs’. Accessed 18 January 2022. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2021-10-19/climate-crisis-international-order-isnt-ready.

[9]. See Carney, Mark. Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon – climate change and financial stability, 29 September 2015. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2015/breaking-the-tragedy-of-the-horizon-climate-change-and-financial-stability.pdf?la=en&hash=7C67E785651862457D99511147C7424FF5EA0C1A.

[10]. Recall Douglas Adams’ “somebody Else’s Problem Field Generator, from Life, the Universe, and Everything.

“An S.E.P. can run almost indefinitely on a torch or a 9 volt battery, and is able to do so because it utilises a person’s natural tendency to ignore things they don’t easily accept, like, for example, aliens at a cricket match. Any object around which an S.E.P. is applied will cease to be noticed, because any problems one may have understanding it (and therefore accepting its existence) become Somebody Else’s Problem. An object becomes not so much invisible as unnoticed.”

[11]. Krishnan, Mekala, Tomas Nauclér, Daniel Pacthod, Hamid Samandari, Humayun Tai, Dickon Pinner, and Sven Smit. ‘A Framework for Leaders to Solve the Net-Zero Equation | McKinsey’. Accessed 19 January 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/solving-the-net-zero-equation-nine-requirements-for-a-more-orderly-transition?cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hdpid=a49d25a0-d35a-469f-af27-924cc9489e19&hctky=12943400&hlkid=e43e1c8f025c4ef483a55309a10e32a1.

[12]. See Edmonds, Timothy. ‘Financial Crisis Timeline’. House of Commons Library Briefing Paper No. 04991 (12 April 2010); and Webel, Baird, and Marc Labonte. ‘Government Interventions in Response to Financial Turmoil’. Congressional Research Service, 1 February 2010.

[13]. Estimates suggest that global fiscal support totaled $13.8 trillion, with $7.8 trillion in incremental spending and forgone revenue and $6.0 trillion in equity injection, loans, and guarantees since March 2020. See: ‘The Territorial Impact of COVID-19: Managing the Crisis across Levels of Government’. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), 10 November 2020. https://doi.org/10.1787/d3e314e1-en.

[14]. Dunz, Nepomuk, Tina Emambakhsh, Tristan Hennig, Michiel Kaijser, Charalampos Kouratzoglou, and Carmelo Salleo. ‘ECB’s Economy-Wide Climate Stress Test’. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3929178.

[15]. See Lewandowsky, Stephan, Keri Facer, and Ullrich K. H. Ecker. ‘Losses, Hopes, and Expectations for Sustainable Futures after COVID’. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8, no. 1 (December 2021): 296. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00961-0.

[16]. See Enhanced cooperation between the United Nations and all relevant partners, in particular the private sector

[17] As a “practice package”, I refer to practices which require one or more supporting practices or industries, which are co-related. So, in this context, the recycling of a given product may require a) the intelligence-gathering and collection, b) a process of transformation (which may require more than one step), and c) an application process using particular outputs of the previous step—not all of these activities may be done by the same entity. It may be that without the full chain of activities, none of the steps in the “practice package” makes sense, so a complete chain needs to rationally exist.